The Indonesian Throughflow is, quite simply, the largest movement of water on the planet. It is the key to understanding the extraordinary marine biodiversity of the Indonesian archipelago and the greater Coral Triangle.

This powerful oceanic current links the Pacific and Indian Oceans, driving a constant exchange of water, heat, and nutrients. So immense is its flow that oceanographers had to invent a special unit to measure it – the Sverdrup.

As David Pickell so clearly describes in his book Diving Bali, the Indonesian Throughflow is not just a current but an entire marine system that shapes life throughout the region.

What Drives the Indonesian Throughflow?

At its core, the Indonesian Throughflow is driven by the difference in sea level between the Pacific Ocean to the northeast and the Indian Ocean to the southwest. This difference arises from global trade winds and oceanic circulation patterns that push water westward in the Pacific.

The resulting pressure imbalance forces massive amounts of water through the complex channels of the Indonesian archipelago. The islands act like a natural “hydraulic brake,” slowing and redirecting the flow through narrow straits and deep basins. It is said that if Indonesia did not exist, there would only be 23 hours in each day because of the sheer drag created by the Indonesian Throughflow!

Measuring the Immense Flow – Sverdrups

Traditional measurements like cubic metres or gallons are far too small to quantify the Indonesian Throughflow. That’s why Norwegian oceanographer Harald Sverdrup created the Sverdrup – a unit representing one million cubic metres of water per second.

To visualise this, David Pickell invites us to imagine a river 100m wide, 10m deep, flowing at 2 knots. Now picture 1,000 of those rivers combined. That’s one Sverdrup!

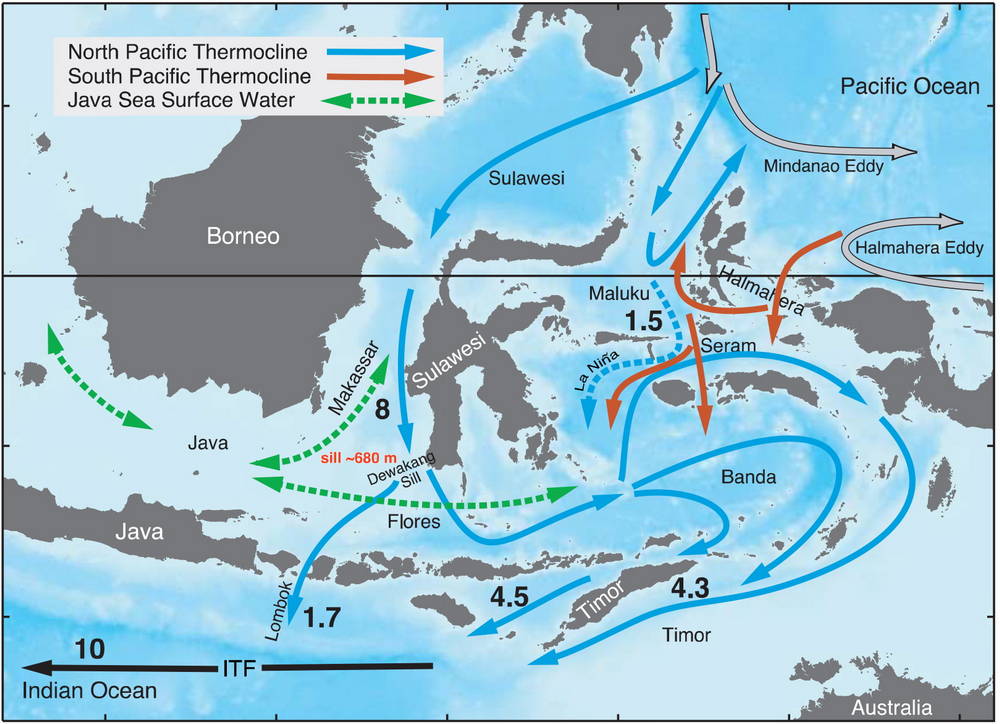

The Indonesian Throughflow moves an estimated 15 Sverdrups — the equivalent of 15,000 of those rivers flowing simultaneously through the island chain. This colossal volume is channelled through the narrow Lesser Sunda Islands, a series of deep passages that serve as gateways between the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

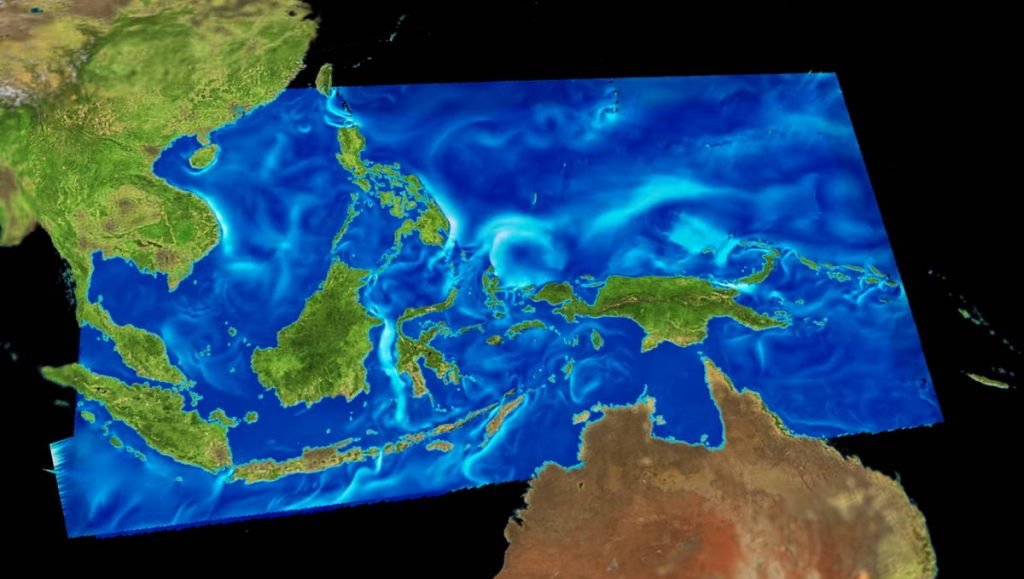

Visualising the Indonesia Throughflow

For a vivid visualisation, software engineer Scott Pearse of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado has produced an excellent Indonesian Throughflow animation, available on YouTube. It beautifully captures how this underwater highway moves through the archipelago – click on the image below to view the animation.

Main Exit Points – The Great Channels of the Throughflow

Only a few key straits handle the majority of the Indonesian Throughflow’s massive discharge.

These include The Lombok Strait, between Bali and Lombok, the Sape Strait, between Sumbawa and Komodo, and the Ombai Strait, between Alor and Timor

Among these, the Lombok Strait, roughly 35km wide, serves as the most direct and significant pathway for water moving into the Indian Ocean. It is estimated that around 20% of the Throughflow passes through this conduit – equivalent to 3,000 rivers.

Biodiversity and the Indonesian Throughflow

The influence of the Indonesian Throughflow goes far beyond oceanography – it is the lifeblood of marine biodiversity throughout Indonesia and the Coral Triangle.

In most oceans, when marine organisms die, they sink to the seabed, decomposing into nutrient-rich detritus that feeds benthic (bottom-dwelling) life. But in the western Pacific, north of Indonesia, something remarkable happens.

As the deep Pacific waters approach the continental shelf of the Indonesian archipelago, upwellings occur – powerful vertical currents that pull nutrient-rich water from the depths back toward the surface.

These upwellings fertilise the region’s reefs and coastal ecosystems, completing a vast natural cycle. The nutrients sustain plankton blooms, which in turn feed fish and larger marine life, creating one of the most productive oceanic regions on Earth.

The Indonesian Throughflow also acts as a biological conveyor belt, dispersing eggs and larvae across thousands of kilometres, connecting ecosystems and replenishing life from Bali to Raja Ampat.

Alfred Russell Wallace and the Indonesian Throughflow

Long before oceanographers understood the Indonesian Throughflow, naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace was uncovering the region’s biological mysteries. Between 1854 and 1862, Wallace explored what was then known as the “Malay Archipelago,” travelling more than 14,000 miles and collecting over 125,000 specimens of flora and fauna.

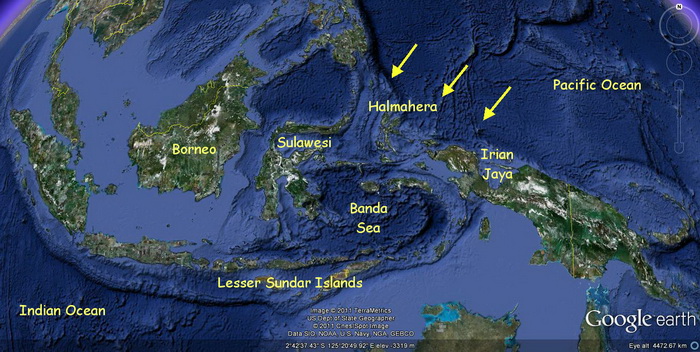

His observations led to one of biology’s great insights: the Wallace Line—an invisible boundary separating Asian and Australasian species. To the west, life was distinctly Asian; to the east, it was unmistakably Australian.

Wallace could not have known it, but the mechanism behind this remarkable biogeographic divide lies partly in the Indonesian Throughflow itself. Over millennia, the strong currents and deep-water channels shaped the distribution of species, reinforcing this natural boundary that remains one of the most profound zoological barriers on Earth.

The Ocean’s Pulse

The Indonesian Throughflow is not just a scientific curiosity—it’s the ocean’s heartbeat. It connects two great oceans, moderates global climate, distributes life, and nourishes the reefs that make Indonesia and the Coral Triangle the epicentre of marine biodiversity.