In many ways the current status of conservation in south-east Misool is an example of what can be achieved by people who are passionate, but pragmatic and find a way through even the most difficult and complicated situations.

Just 10 years ago the area was in decline after being targeted by shark finning operations hungry to tap in to long-liners

Fundamental to the overall strategy was to recognize that the area’s remoteness had allowed it to become a soft target for . As recently as the early 1990’s local villagers say that sharks were very common in south-east Misool, but within 10 years they were becoming increasingly rare as the long-liners reaped their savage harvest!

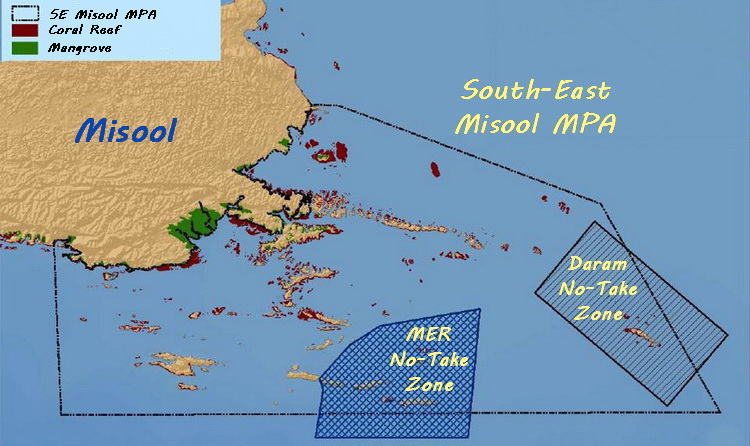

Initiated by the highly commendable efforts of Andy Miners from the Misool Eco Resort (MER) and the establishment of the original 425 sq km MER “no-take” zone around the island of Batbitim, the whole of south-east Misool is now an integrated Marine Protected Area (MPA) encompassing a total area of 3660 sq km.

Integral to the implementation of the MPA were the needs of local villagers who unlike the rest of Indonesia still retain their traditional tenure rights over the sea under the local Papuan Law called Hak Adat – which is accepted by the central government in Jakarta under the special autonomy granted to West Papua in recognition of its somewhat unique status as part of the Republic of Indonesia.

This is a profoundly important element in the long-term sustainability of the initiative because, apart from the Eco Resort and PT Mutiara pearl farm at Yellu, there is virtually no regular employment in south-east Misool and most villagers live a subsistence life-style depending heavily on the area’s marine resources.

Map of the SE Misool Marine Protected Area (MPA) – Image Courtesy of The Nature Conservancy

With the assistance of the The Nature Conservancy and using data gathered from surveys and interaction with the local villages over a 4 year period, the MPA has now been divided up in to a number of zones that take in to account the condition of the reefs and overall fish populations mapped against the needs of the local communities and their traditional Adat laws and Sasi based conservation management practices.

Fundamental to the overall strategy was to recognize that the area’s remoteness had allowed it to become a soft target for the insidious shark finning long-liners. As recently as the early 1990’s local villagers say that sharks were very common in south-east Misool, but within 10 years they were becoming increasingly rare as the long-liners reaped their savage harvest!

Andy Miners solution was to establish a “no-take” zone under the lease arrangement that enabled him to build Misool Eco Resort and, by creating a safe haven, allow nature to do what it does best and let the depleted shark population rebuild.

Convincing the village elders and Adat leaders about the no-take zone required a degree of lateral thinking – not because they did not like the idea, on the contrary they loved it as it aligned with their traditional Sasi practices, but nothing like it had been done before and how to keep out the long-liners in such a huge area?

Andy Miner’s answer to that question was to establish regular patrols of the proposed no-take zone using Rangers recruited from the local villages and two dedicated boats provided by the resort – which convinced the Adat leaders to proceed while creating much needed employment.

This led to the MER zone being established in late 2005, followed 5 years later in 2010 by a similar one in remote Daram.

Significantly the Daram no-take zone came in to being after the community leaders from a second village approached the resort requesting help in creating a conservation area in their tenure area!

Map of the Misool Marine Protected Area and “No-Take” Zones – Image Courtesy of The Nature Conservancy

Map of Misool Eco Resort’s “No-Take” Zone

Under Construction

is patrolled by our team of 10 local Rangers. Using 2 dedicated boats, our Rangers enforce the regulations of our area, which include a complete ban on fishing, netting, shark finning, harvesting of turtles or their eggs, bombing, use of cyanide or potassium borate, etc. Thanks to diligent and relentless patrolling, the incidence of infractions is now extremely low. You can read more about our Ranger Patrol and our No-Take Zone

and one that was answered by establishing

The final version of the zoning plan incorporated agreements at the village level marine conservation agreements (between villages and Misool Eco Resort), and business agreements (between villages and the pearl farm Yellu Mutiara).

Similar to other MPAs in Raja Ampat, the zoning system combines modern conservation science and traditional management practices (sasi) which are not commonly found in Indonesia. Similar to the Kofiau MPA, the zoning plan for Southeast

Misool MPA is a unique example in the Coral Triangle of how to incorporate biodiversity, fisheries and climate change aspects into an MPA management plan

The result is the core area of the MPA, which Misool Eco Resort negotiated when they were first getting established and gives them exclusive rights to Batbitim and Jef Galyu Islands to run their business with a strong degree of surety –

an important element in the ever changing sands of Indonesia…

Then the MER “no-take” zone was negotiated and established in seas surrounding the resort.

Under the provisions of the lease, MER secured In addition, rights were secured to designate approximately 200 sq. km of surrounding seas as a no take zone (NTZ) including animals, coral reefs, turtles, sharks, rays and fish. Under the

terms of the lease, anyone other than MER is prohibited from taking any marine products from the NTZ or granting permission to any other party to do the same.

However, as the demographics of eastern Indonesia have undergone radical changes in the past 15 years the number of newcomers to Papuan villages has increased dramatically. These shifts have shaken the foundations of Papuan communities,

and many traditions, including ‘sasi,’ are disappearing.

the encompasses the superb reefs of both the Sagof-Dalam to the north and the Southern Archipelago to the south.

In 2004, communities, all levels of government, and local and international NGOs came together in partnership to help manage the MPA. Protection for the area began with a legal decree in 2007 that established the MPA. Today, the partners

are implementing six key conservation strategies to ensure the MPA is effectively managed and is delivering benefits to the communities of Southeast Misool.

Southeast Misool is the largest and southern mostmarine protected area (MPA) in the Raja Ampat MPA

The institutionalisation of conservation practice is a more complicated issue. Across Indonesia, conservation is something others profit from. Exploitation of resources pays a pittance, but conservation hardly pays at all, with much of

the profits from conservation concentrated in the hands of local tour operators. In Misool, the centre’s human resources provides locals with a stake in maintaining these activities and the increased catch on the fringes of the zone has

amply demonstrated a tangible value for others in the community.

Local buy-in was vital to make the concept work. Miners negotiated with southeastern Misool’s adat leaders for months before the no-take zone was finally agreed upon. The leaders were keenly interested in the idea. They were not

profiting from the trade in sharks: they were intimidated by the longliners but felt powerless to stop them. They, in turn, convinced their communities of the benefits of the plan.

Buy-in from locals was vital for the success of the no-take zone for cultural reasons, but also to meet legal requirements.

Patrolling the zone

The establishment of the no-take zone led to the expulsion of shark-finning camps and the regulation of boats in the area: boats were allowed to transit the no-take zone, but under no circumstances could they fish there. Local rangers

patrol in donated boats with the blessing of the local security actors, who often actively assist them. When fishing boats are seized, they are impounded and the catches are jettisoned into the water. The boats are held until a fine is

paid.

The patrol have chased off numerous large long liners; the most dramatic capture so far has been two fishing boats from Sulawesi, their roofs covered with drying fins. The boats were caught just after the nets were submerged, and when

the patrol boarded the boats and dragged the nets from the water, entangled sharks were cut free and saved. More common are the seizures of local boats from Sorong: dozens a month have been driven off, and as word of the vigilance of the

patrols spread, the number of seizures has declined to an average of two per month.

The most difficult seizures are the boats from villages that traditionally fished the zone before the adat leaders decided otherwise. Such challenges to adat authority from impetuous young men seeking to establish their own power are

common. But the law is applied to all. In the beginning, the patrols took a ‘soft’ approach to local infringements. Warnings were accompanied by constant socialisation of the reasons behind the no-take zone – food security for future

generations. Fines were not imposed, but catches were confiscated. Meetings were then held in the offenders’ villages, when the elders would discuss the positive impact of the zone. In the last five years, violations have fallen by 90

per cent.

The patrols are now paid by the profits from the resort and from donations: three dedicated boats and a team of local rangers, most of them ex-shark fishermen, operate from three ranger bases. They coordinate patrols with the resort and

with local villages that report boats in the area. In 2010 the zone was expanded eastward to include Daram Island, doubling the size of the zone, and it is now larger than the land and sea area of Singapore.

Rejuvenation

Just as the impact of longlining in Raja Ampat cannot be quantified, neither can the impact of the no-take zone. But it is clear to all. Simply diving the house reef off the Misool pier reveals every common reef species: snappers, a

school of juvenile jacks, giant Malabar groupers, napoleon wrasses, bumphead parrotfish and the occasional great barracuda. Every dive site reveals these, as well as grey reef, whitetip, blacktip and wobbegong sharks, schools of

barracudas and all manner of pelagics. Rare nocturnal epaulette sharks are no longer rare here. The channel that separates Batbitim from a neighbouring island was once renowned by locals for shovel-nosed rays, but they were

systematically netted and finned. However, the population is growing. There are other rarities: blotched fantail rays, Sargassum frogfish, hammerhead, silvertip, and whale sharks.

The protected cove on the north beach now hosts juvenile blacktip sharks learning to hunt, the cove is now a parturition area where mothers give birth. The northwest corner of the cove hosts a colony of mandarinfish, as well as endemic

species such as flasher wrasse and a species of pygmy seahorse found nowhere else on earth. The famed marine zoologist Dr Gerald Allen has discovered numerous new species in the area, including a new stingray with a four-metre disk

width. Until recently, only reef mantas were known to exist. However, in the last four years, scientists have determined that two species exist: Reef (alfredi) and Oceanic (birostris). A third species has possibly been identified. Reef

mantas with wingspans up to five meters are found throughout Misool, but the real stars are the oceanic mantas, with wingspans up to nine metres.

One of Misool Baseftin’s conservation programs, the Misool Manta Project, studies the endemic and transitory ray populations of southern Raja Ampat, taking DNA samples, tagging mantas with radio tracking devices and photographing them.

Radio receivers are moored at depths of 40 to 50 metres at strategic points inside and outside of the zone and are regularly collected, stripped of data, and re-anchored. This provides a fascinating map of these creatures as they move

from station to station. So rich are the nutrients in the water that these receivers are completely encrusted by sponges, molluscs, tunicates, and marine algae within a few months. Only 30 per cent of the individual mantas have been seen

more than once, and the resighting rate of the larger oceanics is just six per cent.

Infractions in the zone

The most effectively patrolled areas of the no-take zone are those that benefit from line-of-sight radio communication between the ranger stations and the ranger patrol boats. Locals constantly report suspect vessels and assist the

patrols to protect their assets. The local fishermen benefit from the zone by fishing just beyond its borders, reaping the benefit from the expanded stocks that spill over into the surrounding fishing grounds. However, the fringes of the

zone are still preyed upon. In Daram, on the far west of the islands, there is evidence of dynamite fishing. Devastated sections of hard coral on top of seamounts and blown out from walls to scatter on the sea floors below: gorgonian

fans and soft corals ripped loose to drift along as they slowly die; an emperor angelfish with its eyes blown loose: wounded red snappers finning ineffectively in the shadows until the barracuda find and disassemble them.

This practice is still found across the archipelago. One boat from Daram threatened an unarmed Misool patrol boat with a bomb. That ship escaped. These villagers also prey on turtles. On Daram’s beaches we saw the drag marks of green

turtles on sand as they climbed toward the tree-line to lay and bury their eggs, followed by the footprints of the men who followed those same trails and dug them up. Green, Hawksbill, and Leatherback turtles are all endangered, the

Leatherbacks critically. When locals catch them, they are killed and eaten. North and south of the zone,only juvenile hammerheads are found, though fewer as the years go by.

This mass killing continues elsewhere: North Sulawesi’s Lembeh strait was once known for sharks and rays, but they were wiped out by a few longliners who stripped the strait of megafauna over a six-month period in the 1990s. It is now

only known for small creatures on the black sand. A few years ago north of the Wakatobi Islands in Southeast Sulawesi, a hammerhead parturition site was found and annihilated in months. And in Bali’s Nusa Penida, pregnant threshers are

being exterminated in a parturition area near Sampalan Beach. The pups, which have no commercial value, are left on the beaches to be eaten by stray dogs. In Ende, in Flores, slaughtering rays is the only growth industry. The Misool no-

take zone is all the more incredible; that clichéd Eden that the adat chiefs remembered is returning.

Understanding Sasi