The Great White Shark, Carcharodon carcharias is one of the ocean’s most magnificent creatures. Superbly evolved, they are truly an apex predator. But, unlike their terrestrial equivalents, there is very little reverence for them.

Instead, and they have become widely demonized as brutal man-eaters that silently prowl our coastal waters. In a seemingly perpetual search for victims and then pouncing with ruthless and terrifying efficiency.

And it is true that great whites have been held responsible for more deaths of swimmers, surfers, and divers than any other shark.

But what is the reality about these creatures? Are they really what the tabloid media have made them? Or are they just greatly misunderstood?

That reality is quite nuanced and very much depends on how you approach it. Because unlike lions and tigers, where the images we see of them often include cute, almost kitten-like cubs that are hungry and need to be fed. Great whites are predominantly shown in a sensational manner that reinforces our preconceptions.

Gaining a better understanding of these creatures requires a bit of work. Plus a degree of patience and a desire go deeper into things that interest you.

The Great White Shark – Where They Roam

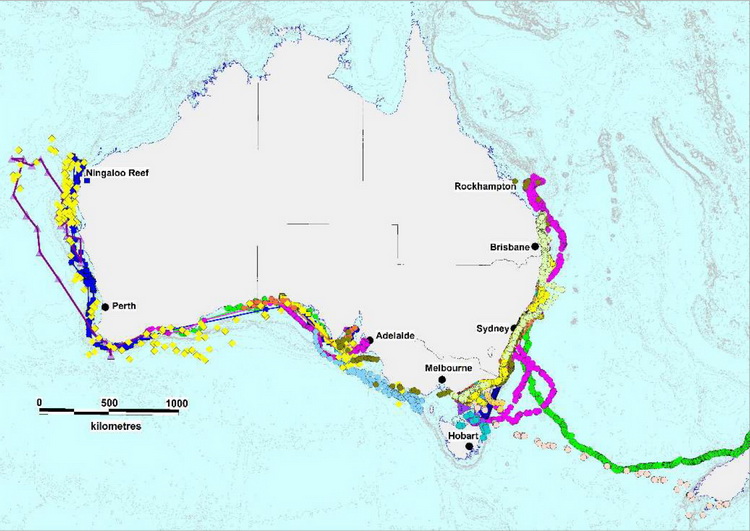

Great white sharks are present in almost all coastal and offshore waters with water temperatures range between 12°C and 24°C. Their largest known populations are found in the United States, South Africa, Japan, Chile, and… here in Australia.

They are epipelagic fish, living in the upper layer of the oceans where marine life is the most abundant. Satellite tagging has shown that while they spend most of the time in less than 200m of water. They occasionally go deep – with one shark recording a depth of 1200m. Why they do that, nobody really knows…

They are also known to migrate significant distances. With tagged sharks traveling between the east coast of Australia and the South Island of New Zealand. And in North America, from Hawaii to Baja California.

Marine scientists believe great whites can navigate those huge distances using the “electro-receptors” in their Ampullae of Lorenzini. The mucus-filled pores on their snout that can detect both the size of an electrical field and its direction. Which they use with the Earth’s magnetic fields to find their way in the vast open ocean.

The Great White Shark – Down Under

Here in Australia great white sharks occur from northern Queensland. All the way down the east coast and around the south coast of Australia. And up to the Montebello Islands in the north-west of Western Australia. Interestingly the CSIRO have established there are two distinct populations.

The east coast sharks, with an estimated total number of about 5500. And a south-western population whose total numbers have yet to be finalized but are thought to be around the same, or possibly more.

Overall, it seems there are probably around 11,000 animals in the roughly 20,000 kms of Australian coastline they are known to roam. Our coastal waters are defined as 3 nautical miles, or 5.5km from shore. So a total area of some 110,000 sq kms. Which means, at best, one great white shark per 10 sq kms of coastal water…

Clearly there are a lot of assumptions and averaging in that back of the beer mat calculation. But you get the picture, they are not that common!

The Enigma

Enigma: “A person or thing that is mysterious or difficult to understand” – if ever one word could be said to describe the great white perfectly, I think it would have to be “enigma”…

Our perception of the great white shark has been greatly influenced by the toxic mixture of Steven Spielberg’s triple academy-award winning movie Jaws and the tabloid media. Jaws was the first major movie to be shot on the ocean and although it ran way over budget, it went on to become a huge success. The movie was based on Peter Benchley’s book of the same name, which he wrote after reading about sport fisherman Frank Mundus’s capture of an enormous shark in 1964.

The movie is said to have inspired “legions of fishermen, to pile into boats and kill thousands of the ocean predators in shark-fishing tournaments” in what was called the Jaws effect. Benchley later stated that he would never have written the original novel had he known what sharks are really like in the wild.

Some Facts…

While Steven Spielberg may have created the Jaws effect, the tabloid media have run with it for decades. Tapping deeper into the vein of fear in our psyche the movie mined so well.

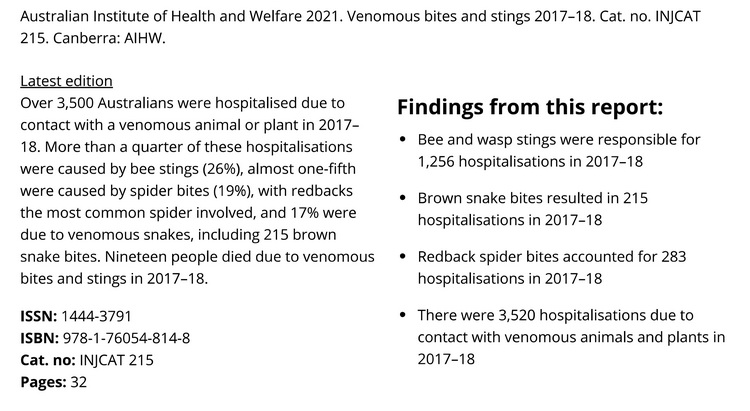

The facts are that you have a greater chance of dying from a bee sting than from a shark attack.

In 2017/18, reliable data from Taronga Zoo shows that 45 people were involved in shark attacks and 2 died as a result.

While, in the same period data from AIHW shows that 927 people were hospitalized because of bee/wasp stings and 12 died.

Such deaths are obviously tragic to all concerned, but when did you last see a death from a bee sting on the evening “news” or the front page of your local tabloid?

The real travesty of all this is the way the “media” use a shark attack to provide cheap content!

Understanding That Enigma

There is absolutely no doubt that great white sharks are completely unpredictable and potentially extremely dangerous animals. But… that is their role in the ocean and they are not some kind of satanically motivated killing machine!

Their behaviour is driven by an instinctive capability to survive. And, as an apex predator, they do what they need to do when they need to do it. But with the ingrained caution and situational awareness their successful evolution has taught them.

Much of that instinctive behaviour seems to be driven by how hungry they are. Which is a function of when they last ate and what they ate.

Based on a ground-breaking (for the time…) US research paper published in 1982, it was long believed that great whites can go for weeks before needing to feed.

But a more recent paper by the University of Tasmania (UoT), indicates that they actually eat much more often.

The difference between the two papers is that the first one used data from a tagged shark feeding on a dead fin whale to calculate its metabolic rate and, from that extrapolate how often it would need to eat.

The Great White Shark – UoT Research

The premise of the UoT research being that the specific great white in the 1982 paper had already found an abundant source of food. Therefore, its metabolic rate would have dropped as it worked leisurely on the “all you can eat” buffet before it.

So, the researchers tagged sharks at the Neptune Islands in South Australia that were actively hunting for seals. And established they had a much higher metabolic rate and would therefore have to eat much more often.

The Readers Digest version of it all is that great whites probably need to eat every day when they are feeding on open-water fish like silver seabream.

Whereas, when they can switch to fat-rich mammals like seals, consuming one every 2-3 days is probably enough.

The bottom line being that the urge to eat and the availability of suitable food is probably the major driver of behaviour and great whites do need to eat quite often.

How often is a function of the nutritional value of what they last ate. Seals are highly nutritious, silver seabream less so but still adequate. While humans provide very little nutrition and are simply not on the shopping list!

The Great White Shark – Seeing for Yourself

Australia is one of only four countries where you can experience in-water encounters with great white sharks. Albeit, from the safety of a custom-built cage. The other three are Mexico, South Africa and New Zealand.

There is only one location here though… The Neptune Islands, two groups of islands that sit on the edge of the Great Australian Bight, near the entrance to the Spencer Gulf.

Both groups are important locations on the great white “super-highway” – their migratory corridor along the southern coast of Australia.

The sharks have waypoints on that corridor where they should be able to feed and the large seal colonies on the Neptune Islands provide a very reliable source of high-nutrition food they can depend on. Particularly so during autumn and winter each year. When recently weaned seal pups are first venturing out into the open waters around the islands!

The Great White Shark – The Neptune Islands

Located some 40 nautical miles (74km) to the south of Port Lincoln. The islands were first sighted by Europeans in February 1802 from the deck of Matthew Flinders’ HMS Investigator as the waters of South Australia were surveyed. They were named Neptune’s Isles for their isolation and because “they seemed to be inaccessible to men”.

That isolation, the shelter the islands provide, and the large resident colonies of New Zealand fur seals and Australian sea lions make them an almost perfect location for great white shark encounters.

Male sharks, which when fully mature reach up to 5m in length, are known to be present there all year round. The big females are more seasonal, arriving around the time the seal pups venture out alone in April and hanging around till August.

Fully mature females are incredible creatures and can reach 6m long, but… that additional one metre in length practically doubles their body weight, making then an amazing, almost Jurassic-like sight to behold!

How It Works…

Given the virtually constant presence of great whites at the Neptunes, and contrary to what you might expect, there are no guaranteed encounters with them. While the boats used by the cage diving operators are, in themselves, a tremendous source of stimulation. Emitting significant noise and electrical signals that may attract curious sharks, “attractants” (a.k.a. berley…) are also required.

These days cage diving is carefully licensed by the South Australian government. And, integral to those licenses are the type and amount of attractants used. Long gone are the days when gruesome “witch’s cauldrons” of horse meat and whale oil were the order of the day.

A daily maximum of 100kg of strictly fish-based attractants are allowed under the licenses. And if a shark actually takes a bait there is a mandatory pause for 15 minutes. All of which is designed to allow the operators to get sharks to the boat and keep then there. But not to induce changes to their natural behaviour.

Overall, the rate for successful encounters is high. But the great whites are very much wild animals and the Neptunes Islands are not a safari park!

The Great White Shark – Down Deep

Cage diving comes in two very distinct flavours – surface and ocean floor. Until last year all of my previous trips had been using a surface cage as that was the only option… It was a great one though, allowing me to see great whites in the flesh and up-close. Over time I moved from the mixture of intense trepidation and downright fear to seeing them as the magnificent creatures they are.

The catalyst for that change was seeing the obvious caution of the older sharks. The seemingly reckless abandon of the younger ones and their overall behaviour patterns of the great whites. Basically, I realised that they weren’t the rabid killing machines the tabloid media would have me believe. And I used to explain all that to my family and friends by saying that you need to see great whites in their “natural environment” to begin to understand them.

Then it dawned on me that if I really wanted to see them in their natural environment. I needed to get some experience in an ocean floor cage. Which led me straight to Rodney Fox who, together with his son Andrew, developed the whole concept.

The Great White Shark – On the Ocean Floor

The ocean floor cage really is the closest you can possibly get to “natural”. At the surface the sharks approach the cage because of all the stimulation present – noise, electrical currents and fish-based attractants. Whereas on the ocean floor their behaviour, approach and attitude is quite different.

Just like lions and tigers can blend in almost completely with their surroundings, the great whites can do the same. Viewed from above, their dark coloration makes them very hard to discern.

While from beneath their white under-belly makes them almost invisible. They use their natural camouflage to great effect in the three-dimensional ocean and are able to appear at the cage almost unnoticed.

They seem motivated more by curiosity than anything else. And your temporary immersion in their domain enables unique insight that is almost impossible at the surface. It truly is a special experience, and I cannot recommend it more highly if you really want to better understand the great white shark!

The Great White Shark – Scuba Diver Article

The Australian edition of Scuba Diver magazine recently published my five page great white shark article and you can use the link to download a PDF copy.