Sperm Whales of Dominica… This special island in the south-east of the Caribbean is home to one of the world’s very few resident populations of sperm whales. And it offers a rare opportunity to observe and photograph these ocean giants in their natural environment.

The sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) has long held a special fascination for me — an immense, mysterious creature whose presence in the deep-sea borders on mythic. To finally swim alongside one had become something of an obsession, a quest that stretched across oceans and over a decade. My third attempt would eventually lead me to Dominica — the rugged “Nature Island” of the Caribbean — but the path there was far from straightforward.

A decade ago, I travelled to the Portuguese Azores, drawn by stories of sperm whales migrating through the deep waters off Pico Island. For ten long days, we scanned the horizon and listened for their clicks and blows. We were rewarded with a few fleeting sightings, and I managed to capture a handful of usable images — just enough to keep the dream alive.

Five years later, I tried again. This time my journey took me to the remote Ogasawara Islands, often called the “Japanese Galápagos,” lying nearly 1,000km south of Tokyo. Getting there requires a 24-hour ferry ride — no airports or shortcuts — and the trip promised encounters with sperm whales in the Pacific’s vast blue deserts. We did see plenty of northern humpbacks and even shared one brief in-water encounter, but the sperm whales remained elusive. Two expeditions, thousands of miles, and still no real connection.

Dominica

Then I heard about Dominica — a small, mountainous island in the eastern Caribbean with an apparently resident population of sperm whales. Unlike most of their kin, which roam the great pelagic expanses of the world’s oceans, these whales seemed to have chosen Dominica’s deep coastal waters as home.

It wasn’t an easy decision. Getting there from Australia takes nearly three days, the in-water permit system is hard to understand, and the cost is significant. Yet the promise of finally spending meaningful time with these ocean giants was too powerful to ignore. I booked two back-to-back weeks, packed my cameras, and began the long journey to the Caribbean.

The Sperm Whale Enigma

Sperm whales are truly oceanic beings – immense, intelligent, and perfectly adapted to the deep. While reports of 20m giants exist, mature males typically reach around 16m in length and weigh about 45 tons, making them the biggest of the toothed whales (Odontocetes) and the world’s largest toothed predator.

At birth, both males and females are around 4m long, but as they mature, the differences become dramatic. Few species show greater sexual dimorphism, with males growing 30–50% longer and can weighing up to three times more than females.

The sperm whales of Dominica are part of this remarkable global lineage – truly cosmopolitan creatures found from the poles to the equator. Yet they favor deep, warmer, ice-free waters, where their preferred prey – squid – thrive in the ocean’s twilight zone. How they find and hunt that prey remains one of the most intriguing aspects of their biology.

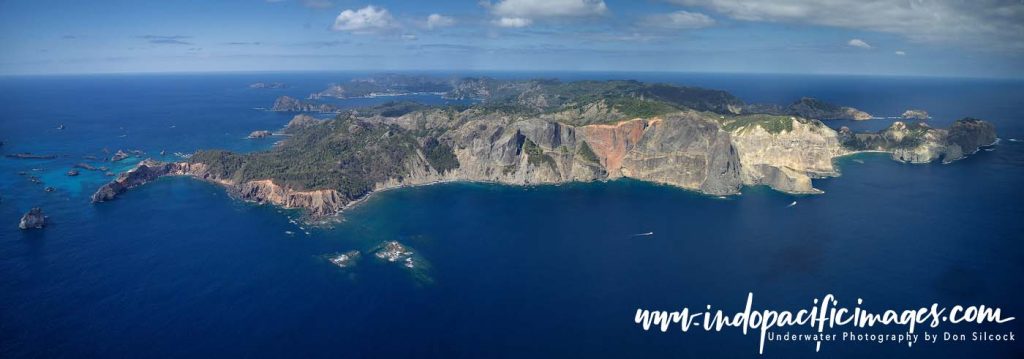

Dominica – The Caribbean’s “Nature Island”

Dominica is unlike any other island in the Caribbean. It’s a rugged, volcanic landscape cloaked in rainforest, with towering mountains, tumbling waterfalls, and rivers that rush straight into the sea. There are no flashy resorts, no crowded beaches or cruise-ship gloss and Dominica feels wild, almost elemental, as though nature still holds sway.

What makes it so unique for sperm whales is the geology that continues beneath the surface. Just offshore, the seabed drops away dramatically into abyssal depths. It’s here, in the deep blue channels between Dominica and neighboring islands, that the whales find the perfect habitat — warm tropical waters above, and an abundant supply of squid below.

This combination of deep water close to shore means that encounters with sperm whales can happen surprisingly near land. In some cases, pods are found just a kilometer offshore, resting, socializing, or diving for food. The females and young appear to remain in these waters year-round, while the large males visit seasonally.

It’s a rare and precious situation — a resident population of the world’s largest toothed whales living within easy reach of the surface and the shore.

Sperm Whales of Dominica – The Hunt…

Life for both male and female sperm whales is a virtually continuous cycle of deep foraging dives followed by short periods of rest at the surface, which for the females and the immature whales in their care, is interspersed with sporadic bouts of “socializing” at the surface.

Because they are such large creatures in almost constant motion, sperm whales need to eat a lot to balance their energy budget, and it has been estimated they consume around one ton of food – or roughly 3% of their body weight – per day.

It has also been estimated that the world’s sperm whale population takes about 75 million tons of food from the ocean per year, which is roughly the same as all the human fisheries!

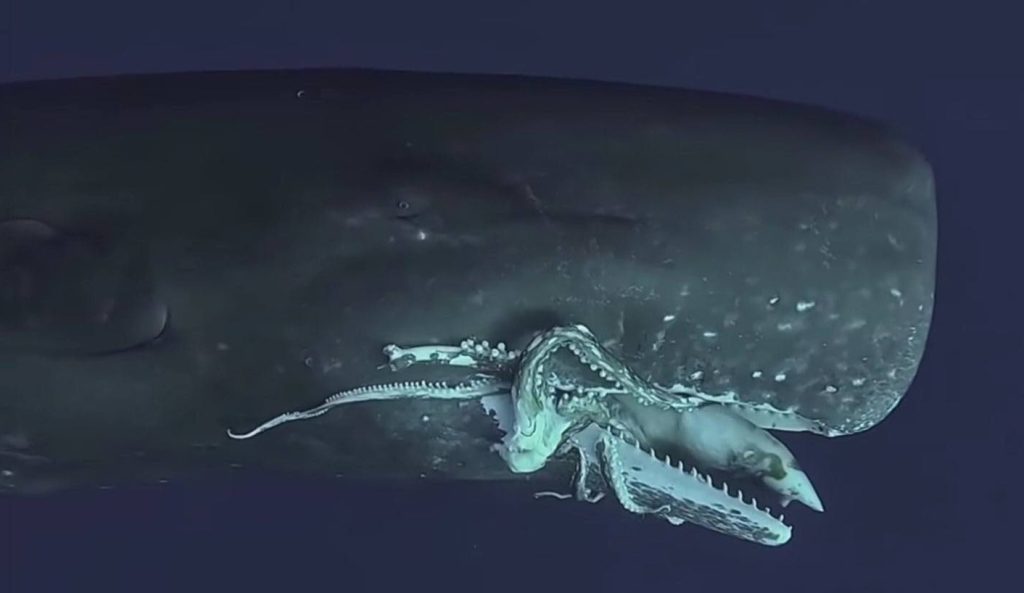

Their preferred squid prey typically inhabit depths of 300 to 800m, and the whales dive for 30–45 minutes at a time to hunt them. Some individuals have been tracked descending to depths of over 2,000m, with dives lasting well over an hour.

Analysis of the stomachs of captured sperm whales indicate that their squid prey ranges from the medium size diamondback squid to both the fearsome giant squid and the quite awesome, cannibalistic diablos rojos (red devils) Humbolt squid, although those most intimidating creatures seem to be only taken on by the large males.

However, all those squid species have suckers that are ringed with very sharp teeth which leave very evident battle scars on many of the whales…

Sperm Whales of Dominica – Sonic Hunters of the Deep

Perhaps the most fascinating thing about the sperm whales of Dominica — at least for me — is how these animals find their prey in the lightless depths of the open ocean. Down there, sunlight doesn’t penetrate, yet the whales can locate squid in the dark with astonishing precision.

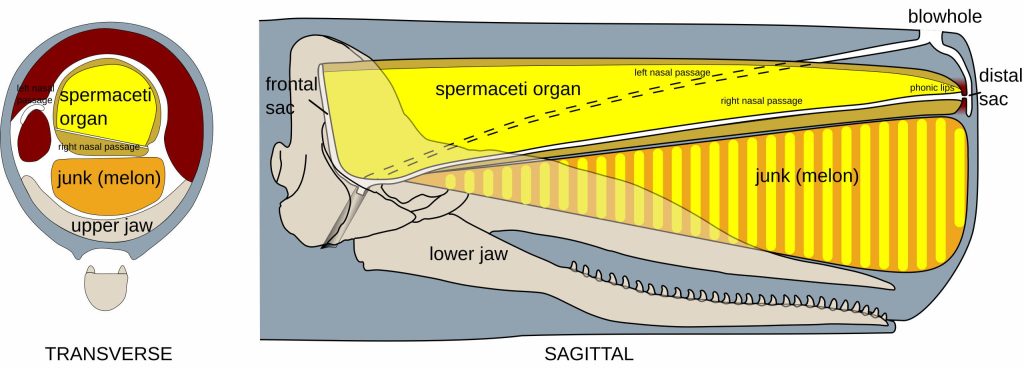

The answer lies in their extraordinary anatomy. The sperm whale’s unmistakable, block-shaped head, which makes up almost a third of its body length, houses one of nature’s most remarkable biological instruments – the spermaceti organ.

This vast organ, filled with a waxy, oil-like substance once coveted by whalers, sits above the whale’s skull and functions as a powerful acoustic lens. Beneath it lies another structure, aptly named the junk, a honeycomb of cartilage and oil that helps focus sound waves. Together, these features turn the whale’s head into an enormous natural sonar system.

By forcing air through a set of muscular “phonic lips,” sperm whales produce incredibly loud clicks, which are among the most powerful sounds made by any animal. Those clicks travel through the spermaceti complex, reflect off internal chambers, and project forward into the ocean as focused beams of sound. The returning echoes reveal everything from the shape and size of distant objects to the subtle flutter of a squid’s fins.

This is how sperm whales hunt, communicate, and navigate the deep – a world of total darkness transformed into an acoustic landscape. Early whalers knew little of this. They named the whale after the “spermaceti” oil they found inside its head, believing it to be semen. In truth, it was this very substance – dense, waxy, and acoustically perfect – that gave the sperm whale its name and its edge as the ocean’s supreme deep-sea predator.

Dual Use…

Some researchers have suggested that the spermaceti organ may also assist with buoyancy.

Noting that as the wax cools and becomes denser during deep dives, it minimizes volume and effort.

Then as the whale resurfaces, metabolic heat warms the wax, increasing buoyancy.

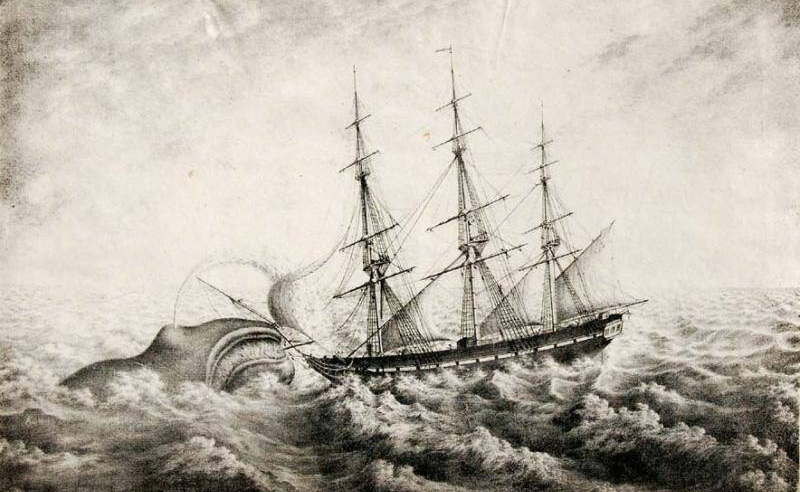

Others believe its massive structure evolved for head-to-head combat between males. Something Herman Melville alluded to in Moby-Dick, which was based on the actual sinking of the whaling ship the Essex by a sperm whale in 1820.

Whichever is true, perhaps both, watching the sperm whales of Dominica dive with their massive heads angled downward as their clicks fade into the abyss, it’s hard not to feel awe. These are not just whales — they are almost living submarines, navigating a world we can scarcely imagine, guided by sound alone.

Sperm Whales of Dominica – Evolutionary Perfection

Sperm whales have evolved superbly for their niche. Their ribs are bound to the spine by flexible cartilage, allowing the ribcage to collapse safely under immense pressure and their circulatory system carries a high density of red blood cells rich in oxygen-carrying haemoglobin, which can be redirected to the brain and vital organs when oxygen levels fall during deep dives.

Their intestinal system, the longest in the animal kingdom, can exceed 300m in large males, and their four-chambered stomach is both muscular and resilient – capable of crushing prey and resisting the claws and suckers of captured squid.

Undigested beaks accumulate by the thousands, and while most are regurgitated, some pass through to the hindgut, where they may trigger the formation of ambergris – one of the ocean’s rarest natural products.

Echoes of the Savanna

It’s often said that the ocean’s great whales are the elephants of the sea — and nowhere is that parallel more striking than in the sperm whale. Both are intelligent, long-lived mammals that live in tight-knit, female-led societies where knowledge, memory, and cooperation are the keys to survival.

Like elephants on land, sperm whales at sea are bound by a deep sense of family. Their societies revolve around matrilineal units — mothers, daughters, and calves who remain together for decades, guided by the wisdom of an elder female. It’s she who leads the group to familiar hunting grounds and safe waters, just as an elephant matriarch might recall the distant location of a waterhole remembered from her youth.

Within these close social circles, the young grow up surrounded by constant care. Sperm whale calves are never left unattended; when a mother dives to hunt, other females cluster protectively around her calf at the surface, forming what researchers call “nursery groups.” Among elephants, the same cooperative care is second nature — aunts and older sisters helping to guide and guard newborn calves while their mother’s feed.

Communication in both species is equally rich and complex. Sperm whales use precisely timed clicks, called codas, to identify themselves and maintain contact across the dark depths. Each social clan has its own distinctive pattern, a kind of dialect that marks cultural belonging.

Elephants, too, are fluent communicators, their infrasonic rumbles carrying for kilometres across the savanna, their meaning understood only by members of the herd.

Life and Death

There is also a deep emotional resonance in how both whales and elephants experience life and death. When a sperm whale is injured or distressed, others will often gather tightly around it, sometimes lifting it toward the surface as if to help it breathe. Among elephants, the parallels are haunting: they have been seen lingering around the bones of their dead, gently touching them with their trunks, and standing silently for long moments as if in mourning.

Even their life trajectories follow similar paths. As young males mature, both whales and elephants must eventually leave the security of their family groups. Teenage bull elephants drift into bachelor herds, learning the rhythms of independence. Young male sperm whales, meanwhile, venture out to form loose associations of their own — roaming the open ocean for years before returning to warmer waters to breed.

And perhaps most remarkably, both species depend on memory — the invisible map encoded in their minds. A sperm whale can navigate across entire ocean basins, recalling deep-water canyons and seasonal feeding grounds with astonishing accuracy. An elephant, too, can remember the precise location of a long-forgotten waterhole or the scent of a relative not seen for years.

Current Population and Conservation Status

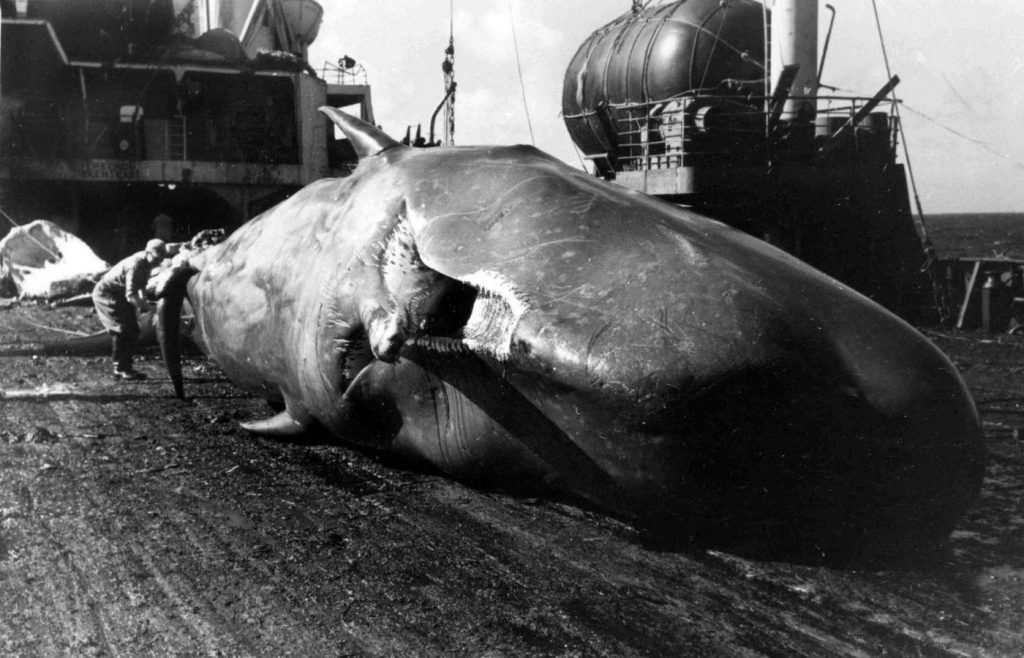

No accurate ecords exist of the worldwide population of sperm whales prior to the start of commercial whaling in the early 18th century, but scientific extrapolations based on the detailed logs kept by the whalers indicate a probable number of around 1.1 million animals.

The sheer global scale of commercial whaling combined with the fact that sperm whales were very lucrative catches, meant that be the time those hunts finally ended in 1986 that population was down to around 300,000.

Recovery from those low numbers has been slow and the sperm whale was reassessed in 2025 for the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as “Vulnerable” with a current global population estimated at between 400,000 and 600,000 individuals.

Sperm Whales of Dominica – Final Thoughts

My time in Dominica turned out to be well worth the long wait. We had in-water encounters with sperm whales every single day during twelve days at sea. Some days were fleeting — “drive-by whalings” as I like to think of them — when whales cruise the surface preparing for their next deep dive.

Others were unforgettable – curious calves approaching closely to inspect us, or large social groups circling and vocalizing together in the blue.

It has been estimated that around 500 individuals, organized into some 35 family groups are resident in the waters surrounding Dominica, part of a larger population that moves along the Lesser Antilles chain, swimming as far south as St Vincent and north into Guadeloupe.

To spend such quality team in and among them was truly a special experience!