The Grey Nurse Shark… Large enough to get your complete and undivided attention. Probably the best way to describe an encounter with a Grey Nurse Shark (Carcharias taurus).

Big and fierce looking, with a set of prominent sharp teeth. Grey Nurse move through the water in a slow but determined manner. Which creates a physically intimidating presence guaranteed to raise the blood pressure of the uninitiated observer.

My first such encounter was many years ago at Flat Rock near Stradbroke Island in Queensland. I was diving the shark gutters on the northeast side of Flat Rock, where Grey Nurse gather from June to October each year.

Although well-briefed on what to do, I have to admit I was more than just a little concerned when I saw the first shark heading in my direction. We had been told not to obstruct the shark’s path, stay calm and just let them swim past. And sure enough the large 3m long female did exactly that – completely ignoring me!

Since that first encounter, I have been fortunate to spend a significant amount of time underwater with Grey Nurse Sharks here in Australia. And at the Protea Banks in South Africa and in Japan’s remote Ogasawara Islands.

And, in all those encounters, I can honestly say that I have never once felt threatened or in any real danger.

So why is it that in just 40 years the Grey Nurse went from being one of Australia’s most common sharks to an endangered species – when it is not even a dangerous shark?

The Grey Nurse Shark – A Bad Case of Mistaken Identity

The 1960’s was a time of increasing prosperity for our “Lucky Country”. With the urban population increasingly using the sea for sport and recreation.

The 1960’s was a time of increasing prosperity for our “Lucky Country”. With the urban population increasingly using the sea for sport and recreation.

Surfing, spearfishing and game fishing became increasingly popular, and the macho image of these water sports suited the times well…

Marine science was also in its infancy, with very little was known about the inhabitants of our coastal waters. Sharks were generally considered to be dangerous creatures.

And large sharks like the Grey Nurse, were automatically assumed to be man-eaters.

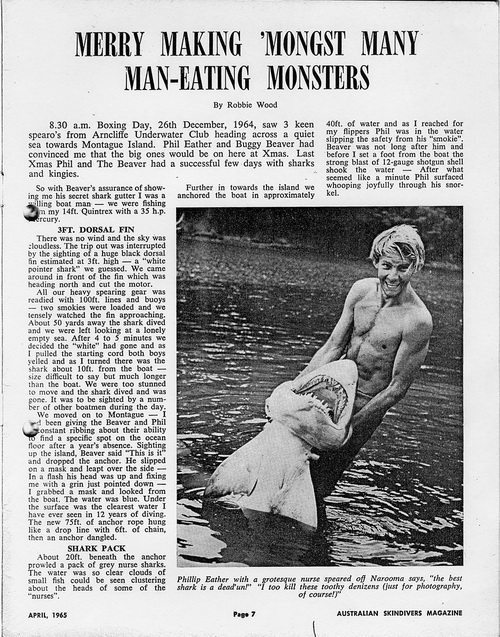

Just as today’s Australian tabloid media automatically assign a shark attack to the Great White. Back in the 1960’s the Grey Nurse was the “usual suspect”.

Catching one of these supposed man-eaters was considered a heroic act and guaranteed a big crowd back on the beach – when the dead shark was hoisted up for all to see.

The Grey Nurse Shark – Persecution

Although predominantly solitary in nature, Grey Nurse sharks gather together at certain times of the year to mate. And such aggregations created the perception that the locations were “shark infested”.

Aggregating together in such a predictable way also meant that Grey Nurse were relatively easy to catch or spear. And the sentiment of the times was the only good shark, was a dead one…

The 1960’s was really a bad time to be a Grey Nurse as later in that decade saw the introduction of the explosive underwater powerhead.

The 1960’s was really a bad time to be a Grey Nurse as later in that decade saw the introduction of the explosive underwater powerhead.

Which tilted the odds well away from the Grey Nurse. In favor of the many spearfishermen using them and resulted in hundreds of sharks being killed.

The impact of that widespread slaughter was two-fold. Initially decimating the Grey Nurse population on the east coast of Australia, but in the longer term it had a dramatic compounding effect.

It takes 6-8 years for Grey Nurse to reach sexual maturity. And once they start breeding the reproductive rate is a maximum of two pups every second year. Meaning that the population grows slowly even when things are normal.

The widespread slaughter of so many mature and sexually active Grey Nurse Sharks in the 1960’s and 1970’s basically threatened the very survival of the species on the east coast of Australia.

That reproductive rate is nature’s way of maintaining the fine balance required to sustain a healthy population. And the carnage inflicted on the adult sharks tipped the balance towards extinction.

All the signs indicated that the sheer number of adult sharks taken meant that it was mathematically almost impossible to restore the overall population.

It really is incredibly ironic that, what we now know as a quite docile shark, could be hunted to the verge of extinction in such a way.

Turning The Tide

Perception, as they say, is reality. And to change the public’s widely held belief that large and intimidating Grey Nurse Sharks are really no more than the labradors of the sea requires exceptional effort.

To get politicians to do anything is even harder. But the latter is virtually impossible until the wheels start to turn on the former.

Australian diving icons Ron and Valerie Taylor were amongst the first to recognize that the Grey Nurse should be protected. Ron, who sadly passed away in 2012, was a former world spearfishing champion who first started spear fishing back in the late 1950’s.

At that time both he and Valerie were convinced that Grey Nurse Sharks were man-eaters.

But over time as they moved more into scuba diving, they came to understand that in reality they were basically harmless. And by the mid 1960’s were actively campaigning for them to be protected.

Ron highlighted two key events that helped to turn the tide of opinion. The first was enlisting the help of Australian game fishing legend Peter Goadby.

Getting Peter Goadby on board added significant weight to the conservation argument by confirming that the Grey Nurse was not a game shark at all.

Game fishermen at that time were not exactly known for their environmental or conservational predisposition… So having such a well-known personality as Goadby on the side of the Grey Nurse was a huge coup.

The second being the Taylor’s 1973 film The Vanishing Grey Nurse. Which went to air as part of a series of 13 thirty-minute documentaries made for Australian TV called Taylor’s Inner Space.

The film broke new ground as it was the first to really explain the Grey Nurse and challenge the perception that it was a dangerous creature.

The Grey Nurse Shark – Protection

The fight to protect the Grey Nurse from extinction was helped by numerous other people. Many of whom went to great lengths, and in 1984 a major breakthrough was achieved when the state government of New South Wales formerly declared the Grey Nurse as ‘vulnerable’.

Making it the first protected shark in the world.

The lead of NSW was eventually followed in Queensland, Western Australia and Tasmania with fisheries legislation to protect the Grey Nurse. And then it was listing as ‘critically endangered’ under Commonwealth legislation.

Face to Face with the Grey Nurse Shark

Underwater encounters with large creatures are always exciting. And the size of Grey Nurse Sharks, together with their physical presence makes interacting with them a truly memorable experience.

Here in Sydney, we are very fortunate to have an annual winter mating aggregation at Magic Point in Maroubra. Just round the headland from famous Bondi Beach.

Magic Point is a really great dive when the conditions are good and is typical of the other aggregation locations I have dived in South Africa and Japan in that it provides a protected area for the sharks during the day.

Grey Nurse mainly hunt at night. Which means they are at their most active when we have no real way of observing them. Instead, we encounter them during the day when they like to hang out in gutters, caves and overhangs to shelter from prevailing currents and potential predators.

Observed this way they seem completely docile and almost kind of dumb. As they patrol slowly round and round in an apparently aimless fashion. But the reality is they are resting and have slowed their metabolism right down to conserve energy. Basically they are almost sleepwalking, or should that be sleep-swimming?

It’s Down to You…

It is really important not to stress the sharks by getting in the way or harassing them. Do that and you will be rewarded as they get used to your presence.

It is really important not to stress the sharks by getting in the way or harassing them. Do that and you will be rewarded as they get used to your presence.

Personally, I always find a good spot for photography and then settle down and wait for the sharks to come to me.

As you do that you will notice that those apparently aimless swimming patterns are actually not random at all.

The patterns are all about maintaining a degree of “personal space” between the sharks. And the amount they need seems to be a function of whether they are stressed or not.

Signs of stress are gaping of their mouths, indicating an increased breathing rate. Together with the speed at which they flick their tails.

The two are linked because an unstressed Grey Nurse will swim in a relaxed manner at a rate that provides enough oxygenated water passing through its mouth and over its gills.

A stressed shark on the other hand has to move faster to increase the flow of water through the gills. And initially “gapes” its mouth to boost the oxygenation effect.

So, it’s very much in the shark’s and your interest to let them settle and come to you!

In Summary

Sharks are a greatly misunderstood animal in general. And the Grey Nurse is possibly the most misunderstood creature in Australia, and it paid a heavy price for that misunderstanding!

While there are some positive signs with the overall population health of the Grey Nurse. It is still Critically Endangered on the east coast of Australia and there is a long way to go…

The basic fact is that as divers we are extremely luck to be able to see these wonderful sharks in their natural environment. And we owe it to them to respect them for the magnificent creature they are.

The Grey Nurse Shark – Scuba Diver Article

The Australian edition of Scuba Diver magazine recently published my four-page Grey Nurse Shark article and you can use the link to download a PDF copy.

Back To: Australian Grey Nurse Guide